A few months ago, I was giving at talk at Powell’s bookstore in Portland, blathering on as usual about all the mythical grammar “rules” out there – stuff like “you should never split an infinitive,” “you should never end a sentence with a preposition,” “you should never use 'nauseous' to mean 'nauseated.'” All of them pure BS.

I realized these false rules have something in common with the bits of usage minutiae that also happen to be true – stuff like, “don’t use ‘enormity’ to mean bigness because it really means great evil or wickedness.” Right or wrong, such tidbits all provide the disservice of overwhelming people. Someone who sets out to “learn” grammar is pelted from all directions with little snippets of info that, together, make it seem impossible to ever get a handle on the whole business.

As I said to the people gathered at Powell’s, it’s important to distinguish between the stuff you really should know and the stuff that need not be committed to memory – stuff that even the experts look up. Anyone who wants a good grasp of grammar should get an education in the basics and just keep a good usage guide handy for the millions of little bits of minutiae.

A woman in the back raised her hand: “So how do we learn the basics?”

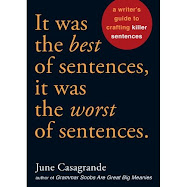

The irony, of course, is that I was standing in a bookstore. Walk into any bookstore and you’ll see beaucoup books about grammar, language, and usage. Fun books, funny books, quirky books, word lovers’ books, dumbin’-it-down books, handy-dandy compendia of notable fact books. These books (and I count mine among them) are great for certain readers. But the person who wants not to read about grammar but to actually learn it – someone who wants a comprehensive grasp of the basics – is often buried in a sea of quirky grammar girls (present company included) and members of the apostrophe police.

So, for the first time, I stopped to consider what, exactly, I would recommend to the person who wants to master grammar and usage. A three-pronged approach came to mind – luckily in time to answer the woman’s question.

As I told her:

1. Learn about the parts of speech, especially adverbs. The resource I recommend: http://www.grammar.uoregon/. It’s free (until they realize how much traffic they’re getting from recommendations like this one), smart and very reader friendly.

2. Learn about phrase and clause structure. The resource I recommend: Oxford English Grammar. Dry as croutons, painful even, but worth the effort. I believe that a basic understanding of phrase and clause structure is perhaps the most powerful way to improve writing. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language is a competing title authored by highly respected experts, but it’s really pricey and usually wrapped in plastic at the bookstore. So I have yet to pony up the dough or muster up the cajones to tear into one. While you're in Oxford, also read up on tenses, so that terms like "past progressive" lose their power to strike fear in you.

3. Have handy a good dictionary and a good “usage” guide.

When choosing a dictionary, be aware that they often disagree and that different publications consider different dictionaries to be “official.” Webster’s New World College Dictionary is the default dictionary of the Associated Press Stylebook. The Webster’s with “Collegiate” in the title is the default dictionary of the Chicago Manual of Style. American Heritage’s current (third) edition is also excellent, arguably better than the other two. Read the front of your dictionary to understand what the little symbols mean and the dictionary’s approach to listing things like plurals, irregular verb inflections, comparatives, and stuff like that.

Dictionaries are much more useful than most people realize. They're not just for looking up spellings and definitions. For example, when someone asked me recently whether "youth" can be used as a plural, my source was a dictionary (both "youth" and "youths" are fine, I learned). Want to know how to put "today I lie down" in the past tense? It's right there in the dictionary, where the past tense of "lie" is shown to be "lay" and its participle is shown, too: "lain." Dictionaries also help with preposition choices, helping you choose between "dissent from" or "dissent with."

Usage guides, though listed here last, are probably the most important – they're most likely to save your butt when you sit down to write something. The resource I recommend is Garner’s Modern American Usage, which is excellent and which seemingly is becoming the preferred source of experts. There are other good ones, including Fowler’s, Webster’s (Usage Guide, that is) and Follet’s. What’s important is that they contain the word “usage” in the title and that you understand what a wealth of information these guides offer you. They’re basically an alphabetized list of answers to practically every usage and grammar question you could imagine.

If you buy just one book, make it one of these usage guides.

(And, in case my publisher’s reading: My books are great sources for people who need a little extra incentive to read about grammar. The incentive being entertainment. So if you find you can’t get past page 1 of “Oxford,” give mine a try. How’s that, Penguin?)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

"When choosing a dictionary, be aware that they often disagree and that different publications consider different dictionaries to be “official.”

Good tip, I didn't know this - thanks. Joe

Post a Comment